One of the most common questions when an employer looks to join a medical stop loss captive is: “Why do I need to post collateral in addition to the premium I pay?” The need for collateral is a major difference between a captive program and a traditional insurance program, and this can be a hurdle to companies joining the captive. In this article, we outline why collateral is needed, how much, and the different forms in which it can be provided.

Why Do Captives Need to Post Collateral?

A captive insurance company is licensed under regulations specific to captive insurance companies. These regulations are not as strict as those that apply to commercial insurance companies. They recognize the fact that a captive insures the risks of its owner(s) and generally imposes lower capitalization and reporting requirements. The captive is typically only licensed in its domicile, and only as a captive insurer. It does not have a license to operate commercially.

Without a commercial insurance license, the captive operates in one of two ways:

- Deductible reimbursement: Mainly applicable to single-parent captives, where the parent organization self-insures to a certain level and the captive provides a reimbursement policy for risk within the deductible. For regulatory compliance purposes, the parent’s self-insurance, or retention under its commercial policy, applies.

Q: Why is collateral needed?

A: So the fronting company can receive credit for reinsurance placed with the captive.

- Reinsurance of a commercial insurance company: In this structure, a commercial insurance company issues a direct policy and reinsures a layer of the risk to the captive. This structure is used where there is a need for a commercial insurance company to satisfy outside parties, or in group captive programs where the captive does not have a license to sell directly to prospective employers.

In the latter case, in addition to not being a commercially licensed insurance company, a captive is not an authorized reinsurer. This is a status defined by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC). Insurers will only receive credit for reinsurance in their statutory returns to the NAIC if that reinsurance is placed with authorized reinsurers or is backed by acceptable forms of collateral. To get credit for reinsurance ceded to captives, insurers will require collateral. Not getting credit for reinsurance is referred to as a “Schedule F” penalty (after the section of the NAIC statutory return dealing with reinsurance).

Posting collateral is a means of managing the credit risk of placing reinsurance with a captive. It supports the ability of the ceding insurance company to recover under the reinsurance agreement with the captive. This is a statutory requirement imposed on commercial insurers by the NAIC and is non-negotiable if those commercial insurers want to avoid a Schedule F penalty.

How Much Collateral Do I Need

If reinsurance is placed with an unauthorized reinsurer, such as a captive, the requirement under Schedule F to avoid a penalty is for collateral equal to 100% of the amount recoverable under the reinsurance agreement. What is the total amount recoverable? For uncapped reinsurance agreements, this is an uncertain number. As a result, most captive reinsurance agreements for medical stop loss include an aggregate limit. This caps the captive’s total underwriting obligations and provides a certain amount for the calculation of the collateral. This captive aggregate is separate to the employer aggregate, which applies in the primary employer stop loss policy.

Q: How much is needed?

A: The captive aggregate minus the net ceded premium.

In percentages: 20-25% of net ceded premium, which typically equates to 10-15% of gross premium.

For most stop loss captives, the captive aggregate is at 120% or 125% of the net ceded premium. The net ceded premium is calculated as the premium ceded to the captive from the fronting carrier minus the ceding commission and captive expenses. It represents the funding available to the captive to pay claims.

In addition to the net ceded premium, collateral is required to cover the gap between the net ceded premium and the captive aggregate.

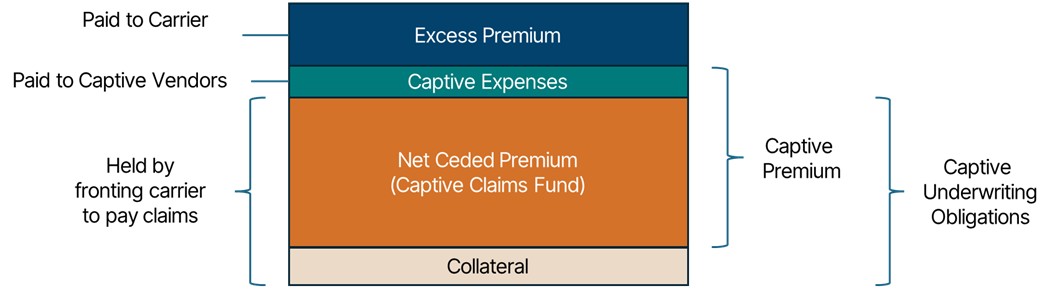

Exhibit A: Captive Funding

Exhibit A shows the overall funding in a captive program. The net ceded premium of the captive (or the claims fund) and an additional 20 or 25% (the collateral) cover the captive’s underwriting obligations up to the captive aggregate. The net ceded premium and the collateral are typically held by the fronting carrier to pay claims.

Providing funds up to the maximum of the captive’s underwriting obligations is referred to as a fully funded program. In addition to satisfying the fronting company’s Schedule F requirements, it also reduces the risk of insolvency for the captive. This provides more comfort to the captive regulators, who may be prepared to waive certain requirements— such as an actuarial review—for fully funded programs.

Forms of Collateral

NAIC regulations recognize three forms of acceptable collateral: cash, letters of credit, and Regulation 114 trusts. Most fronting carriers will allow any of these forms of collateral to support captive reinsurance for medical stop loss.

Cash

Cash is the most common and the simplest form of collateral. Funds are withheld by the fronting carrier equivalent to the net ceded premium. Captive expenses are paid to the captive to allow the captive to pay its expenses. The fronting carrier will pay claims from the funds withheld.

Q: How do I provide collateral?

A: Three options:

-

- Cash

- Letter of credit

- Regulation 114 trust

In addition to the 100% of net ceded premium withheld, the fronting carrier will collect cash collateral to cover the gap to the captive aggregate. Cash collateral is typically billed by the captive manager to the participating employers. The captive manager will remit the cash collateral to the fronting carrier. Collateral may be collected and paid by the captive either annually, quarterly, or, if acceptable to the fronting carrier, monthly.

One of the arguments against cash collateral is that it ties up funds on which the employers could earn interest. Given the short-term nature of stop loss, the funds required to support collateral would need to be fairly liquid and attract low interest rates. To counter this argument against providing cash, many fronting carriers will pay interest on both the funds withheld balance and the cash collateral at a specified interest rate, such as a T-bill rate. The interest is typically factored into the treaty reconciliation when the fronting company calculates the final funds withheld balance and unused collateral.

When negotiating collateral and funds withheld arrangements, make sure to understand what interest the fronting company will pay on funds held in cash.

Letters of Credit

The major alternative to cash as a form of collateral is a letter of credit (LOC). An LOC is an agreement issued to the fronting carrier by an NAIC-approved bank that guarantees the availability of funds to satisfy a payment obligation. In stop loss programs, the LOC is usually issued to cover the gap collateral between the net ceded premium and the captive aggregate. It is typically used in conjunction with a funds withheld arrangement, whereby the net ceded premium is withheld by the fronting carrier and the captive meets its collateral obligation through an LOC. If claims exceed the funds withheld balance, the fronting carrier, as the beneficiary under the LOC, can draw the funds from the issuing bank.

An LOC is a simple, one-page agreement that has three parties: the issuing bank, the insurance carrier (beneficiary), and the employer or captive (applicant). The LOC is typically issued for a specific dollar amount directly corresponding to the amount of the collateral required under the captive reinsurance agreement. Banks typically require a pledge of cash or highly marketable (liquid) securities from the employer/applicant as funding for the LOC. The bank will also charge the applicant a fee based on the amount of the secured obligation for issuing the LOC.

An LOC usually needs to be irrevocable and unconditional in structure. An irrevocable LOC cannot be canceled or modified without the agreement of each of the three parties. LOCs typically expire one year from the issuance date, however, most ceding insurers will require an evergreen clause, which automatically renews.

The benefit of LOCs is that they allow the captive or the employer to earn interest on the funds supporting the LOC. The downside is that there is a cost involved with the LOC, and, in addition, an administrative cost may be incurred in adjusting the LOC. As a result, LOCs backing collateral are typically issued annually with few, if any, adjustments during the year, despite any changes in the number of employees and dependents enrolled in the program. The investment of assets pledged to fund the LOC is not as restrictive as is applicable for reinsurance trusts. The potential for a more favorable investment return can offset the higher charges associated with issuance of an LOC.

The requirement to provide collateral is created by the reinsurance agreement between the fronting carrier and the captive. Following the contractual relationship, the LOC should be provided by the captive to the fronting carrier. This can create a situation of having back-to-back LOCs, in which the employer provides an LOC to the captive to support its collateral requirements, and the captive then turns around and provides an LOC to the fronting company. This increases the cost of the LOC arrangement, and some carriers may be comfortable with an LOC directly from the participants referencing the captive. This approach adds some administrative burden on the fronting carrier in managing the LOC and potentially leaves the captive in the dark on what kind of collateral has been provided.

Reinsurance or Regulation 114 Trusts

A third option for collateralization is a reinsurance trust, sometimes referred to as a Regulation 114 trust. (It is governed by Regulation 114 of the New York Department of Insurance.) A trust is established by the captive, and an agreement is entered into between the captive, the issuing carrier, and a bank. The bank serves as the trustee for the fund in this type of arrangement. As with an LOC, the insurer is named as the beneficiary. Yet unlike the LOC, which typically only covers the gap collateral, a reinsurance trust can cover the funds withheld or the net ceded premium as well. Ceded premium (minus captive expenses) is paid into the trust together with the collateral contributions, and claims payments are then pulled from the trust.

Due to increased complexity and more restrictive funding limitations, reinsurance trusts are not as widely used as cash or LOCs. The trust agreement can be lengthy (up to 25 pages), and funding of the trust is conservative, limited to cash or highly rated ( “A” or higher) marketable securities that can be easily converted to cash.

Reinsurance trusts are less expensive than LOCs; however, the reduced potential for asset investment returns may make them less efficient from a net expense standpoint. In addition, beneficiary approval is required to disburse assets from the trust, which can delay the release of excess collateral being held by the fronting carrier.

Still, if you can get the fronting company to pay interest on funds withheld and cash collateral, there may be little benefit to either LOCs or reinsurance trusts.

Stacking & Release of Collateral

One of the major challenges with collateral supporting captive programs is the potential for stacking across underwriting years. The requirement to provide collateral will renew each year with a new reinsurance agreement. If collateral is still tied up under old years, the captive and its participants will need to post additional collateral. This is known as “stacking” and represents the mounting of collateral one year on top of the prior year(s).

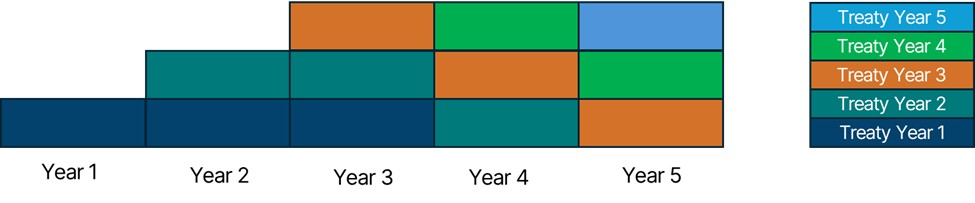

Exhibit B: Collateral by Treaty Year

The example above shows the effect of collateral release 36 months after the start of the treaty year. The total collateral requirement levels out after three years, representing a need of three times the initial year’s collateral. While this situation is quite common with property and casualty captives, medical stop loss has a shorter tail, and captives underwriting this line of coverage would expect to release collateral a little earlier, especially for group captives that have a common expiration date.

Captives that use a risk-attaching reinsurance agreement will run longer and have more collateral stacking. “Risk-attaching” refers to reinsurance agreements that allow 12-month policies, incepting at any date throughout the year. For the reinsurance treaty, this creates a coverage period of up to 24 months, in which the treaty will cover claims in the primary stop loss policies.

Release of Collateral

It is important to mitigate the stacking of collateral in a captive program to reduce the burden on the participating employers. The more this can be seen as an initial investment only, rather than an annual commitment, the more attractive the program. Fronting carriers will start to look at reconciling funds withheld and collateral balance six months after the expiration of the last policy attached under the captive reinsurance agreement. This reconciliation includes both the funds withheld balance (the surplus of the captive claims fund after all claims have been paid) and the collateral. At this point, assuming experience has been good, funds should start to be released. If there is a significant funds withheld balance, it would be appropriate to release the collateral, as there would be little likelihood of exceeding the funds withheld balance. Releasing the collateral as early as possible in the year will limit—or even eliminate—stacking. Releasing the funds withheld balance is a different issue, and there are reasons, such as RBP negotiations, why all parties may want to delay releasing all the funds.

As with most issues in running a successful medical stop loss captive, managing collateral mainly comes down to managing the claims costs in the program. Collateral is required to cover worse-than-expected claims experience. No amount of tweaking, negotiation, or changing the form of collateral will make up for poor claims experience. Good claims experience, on the other hand, removes the need for additional collateral.